curatorial selection by Kateřina Svatoňová

Camera gesture as a possibility of seeing/thinking about the world in a different way.

Camera awareness

We are in an age when the moving image overlaps our everyday life. The fictional world has merged with the real to such an extent that collective and individual memory is now more a recollection of artificial constructs than of actual experiences, and the moving image has so permeated us that it affects all areas of our perception, vision, and experience. Within the variously oriented discussions, there is a virtually unanimous affirmation of the superior role of film, regardless of whether or not the theoretical debat considers it a dead medium. David N. Rodowick points out that film itself may disappear, but not cinema, not least because the narrative structure we recognise as classical narrative film persists and remains firmly embedded in our media subconscious. The key role of film is then confirmed by theories that, following Anna Friedberg, claim that film has permanently changed our perception and vision, or rather that we are no longer subject to the "consciousness of the camera" and are unable to think and perceive in any other way than cinematically, which is why we write and depict cinematically, as Mieke Bal notes. According to Malte Hagener, film is no longer (in human perception) indistinguishable from reality, whereby "we live in images all the time, and images live in us", and, referring to Deleuze and Guattari, he argues that we are in an era of media denomination, whereby there is no longer any transcendental horizon from which to judge the ubiquitous mediated expression.

Dystopian Utopia

We have thus fulfilled the notions of film/camera that the interwar avant-garde proclaimed and which they endeavored to exploit as much as possible in their work. For the French avant-gardists, it was the film camera that could have transformative powers, allowing them to transform an ordinary world into the poetic with unprecedented inner power and energy, to open up its surface and approach another (fourth) dimension, space-time, or to reveal the inner beauty and profound world of things. The camera in the Russian rendition could have fulfilled an even more radical role — it could have become a new sight for the new man, replacing his poor and faulty senses, it could have rethought the world and reconstructed it. Interwar Germany, in turn, related to the camera as a way of approaching the optical unconscious. The contemporary overlay of the world with the moving image, the replacement of our senses with the cinematic, and the structuring of human thinking with cinematic/cinematographic thinking would certainly make the avant-gardists happy. The original utopian ideas have become reality, showing us daily that the fulfilment of utopia can mean dystopia.

Camera gesture

Although our culture, human relationships and attachment to the world are largely determined by film narrative, our thinking and understanding of the world is, on the contrary, influenced and shaped by the image, or rather the gesture of the camera — the choice of visual material, the way of shooting, movement, colour, focus and blur. We can refer to Willem Flusser: "It is not true that writing captures thought. Writing is a way of thinking. There is no thought that is not expressed by a gesture. [...] Strictly speaking, we cannot perform thinking without performing gestures. [...] Having written thoughts means nothing." Thus, mediation itself is a particular (and always specific) way of thinking things through, which is hard to translate into another thought structure and hard to see as something independent of thought.

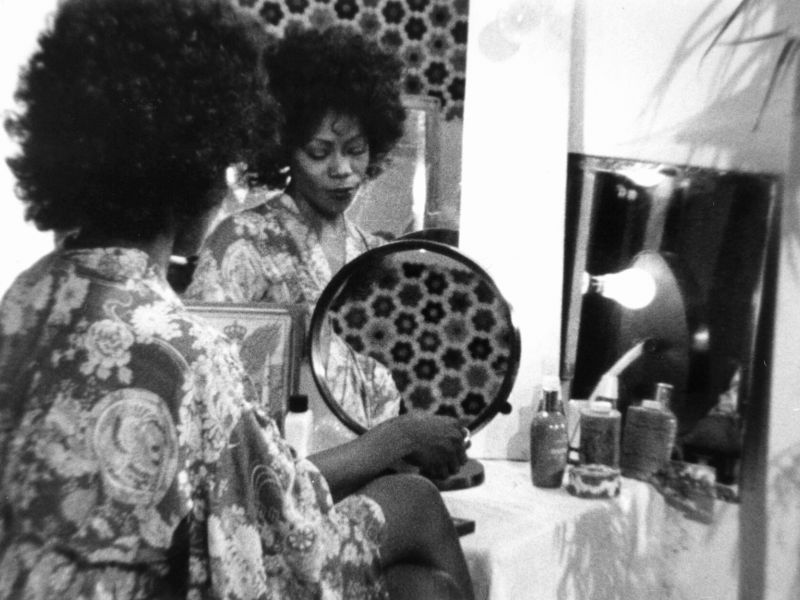

There is a short film depicting Flusser thinking about mediality — wherein the philosopher engages in a dialogue with the camera, points to it, lets himself be shot from different angles, and watches it. He comments that it may not be only language that is a figure of thought in its own right, but that the cinematic image can play the same role. Thus, camera shooting can be a possibility of thinking with film, or thinking through film, it can be a different way of expressing/demonstrating theses and concepts, their contradictions, and mutual consents.

Different thinking

Avant-garde thinking, along with the Flusserian gesture, suggests that the camera need not/cannot be used only as a tool to capture reality and construct seamless narratives, but that it can be used to think elsewise/differently - subversively, expressively, experimentally, performatively. The disruption of the established practices of film language undermines the seemingly realistic impression of the film spectacle and draws attention to the reality of itself, the media gesture, the figure of thought of the film apparatus and material. The series of (counter)shots established by classical film narration can be disturbed by long shots or shots conducted in unusual directions, distances and angles, panoramic camera rotations, shooting with the help of atypical devices, techniques, and technologies. The moving image becomes not only extraordinarily physical and material, but also of thought; a film that contemplates itself, an autopoietic system, a self-movement of the film form that is not only a way of representation, but also a method of philosophical reflection. The camera thus becomes a (self-)reflexive gesture, a lateral gaze that reveals the possibilities of capturing and imaging and allows us to better reveal the reverse side of visible phenomena. Film as a closed space of mediation is opened. Thinking of such a stylized and performative film then provokes various phenomenological and ontological themes. The medium (the film) that has covered our perception/vision is not covered, but constantly reveals itself to us, allowing us to think with and through the film about our own situation in a media-saturated world.

Freeing the Camera

The present time (of many crises) is not only losing its originality and authenticity but is gradually leading to an alienation of the self and to the constant insinuation that anthropocentric and superior thinking about the world is only a rationalistic construct and may not last forever. More and more, we are forced to think about the world outside the subject, to think about the world without man, the world-without-us, about the thinking of others, but also about materiality as such, which is distancing itself from the human scale. The boundaries between the living and the non-living, the organic and the inorganic, the human and the non-human, as well as the ordered and the controlled and the non-orderly and the random, are beginning to dissolve. In this world, the camera may no longer be just a tool in the hand of the creator and a possibility of transforming vision in the manner of the avant-garde, but it can largely detach and become independent, productive, and performative. Its trajectory can be determined by wind or water flow, it can be triggered by automatic sensors, subject to non-living or non-human "cameramen". The technical images that have been perceived as "ours" exist to a large extent outside us and reach completely different (cosmic?) dimensions. Technique and technology thus direct our attention (independently from us) to dimensions of the living or inanimate world that are difficult, if at all, for us to capture in the form of theoretical concepts and considerations. The unusual camera views can then be combined or replaced by digital technologies that allow even greater escape from human influences and perspectives, from the representational function and existing reality. The artists' thinking and seeing is not superior to the image, but seeks to approach hitherto unimaginable structures, non-human media and materialities, and inorganic processes.

Utopian dystopia

Is it a utopia or a dystopia? Does the need to change the current thinking mean disaster, or can it be seen as a new opportunity? Wasn't/isn’t dystopia rather the "kinetic utopia" that Peter Sloterdijk writes about, which assumes that all world movement is merely the realization of our plans, and that nature continuously submits to human desires? What happens in the moment when it is — like the camera's gaze — so exhausted that it must change direction and hegemony? How can the moving image, to quote Donna Harraway, help us with this reversal of the non-order of "natural culture"? What can it show us, how can it prepare us, and what reflective figure can it provide? Can we get carried away by images and forget our usual structures of thought, oppositions, and obvious truths?

Let's try to follow the camera and its opinion.

Kateřina Svatoňová

Camera awareness

We are in an age when the moving image overlaps our everyday life. The fictional world has merged with the real to such an extent that collective and individual memory is now more a recollection of artificial constructs than of actual experiences, and the moving image has so permeated us that it affects all areas of our perception, vision, and experience. Within the variously oriented discussions, there is a virtually unanimous affirmation of the superior role of film, regardless of whether or not the theoretical debat considers it a dead medium. David N. Rodowick points out that film itself may disappear, but not cinema, not least because the narrative structure we recognise as classical narrative film persists and remains firmly embedded in our media subconscious. The key role of film is then confirmed by theories that, following Anna Friedberg, claim that film has permanently changed our perception and vision, or rather that we are no longer subject to the "consciousness of the camera" and are unable to think and perceive in any other way than cinematically, which is why we write and depict cinematically, as Mieke Bal notes. According to Malte Hagener, film is no longer (in human perception) indistinguishable from reality, whereby "we live in images all the time, and images live in us", and, referring to Deleuze and Guattari, he argues that we are in an era of media denomination, whereby there is no longer any transcendental horizon from which to judge the ubiquitous mediated expression.

Dystopian Utopia

We have thus fulfilled the notions of film/camera that the interwar avant-garde proclaimed and which they endeavored to exploit as much as possible in their work. For the French avant-gardists, it was the film camera that could have transformative powers, allowing them to transform an ordinary world into the poetic with unprecedented inner power and energy, to open up its surface and approach another (fourth) dimension, space-time, or to reveal the inner beauty and profound world of things. The camera in the Russian rendition could have fulfilled an even more radical role — it could have become a new sight for the new man, replacing his poor and faulty senses, it could have rethought the world and reconstructed it. Interwar Germany, in turn, related to the camera as a way of approaching the optical unconscious. The contemporary overlay of the world with the moving image, the replacement of our senses with the cinematic, and the structuring of human thinking with cinematic/cinematographic thinking would certainly make the avant-gardists happy. The original utopian ideas have become reality, showing us daily that the fulfilment of utopia can mean dystopia.

Camera gesture

Although our culture, human relationships and attachment to the world are largely determined by film narrative, our thinking and understanding of the world is, on the contrary, influenced and shaped by the image, or rather the gesture of the camera — the choice of visual material, the way of shooting, movement, colour, focus and blur. We can refer to Willem Flusser: "It is not true that writing captures thought. Writing is a way of thinking. There is no thought that is not expressed by a gesture. [...] Strictly speaking, we cannot perform thinking without performing gestures. [...] Having written thoughts means nothing." Thus, mediation itself is a particular (and always specific) way of thinking things through, which is hard to translate into another thought structure and hard to see as something independent of thought.

There is a short film depicting Flusser thinking about mediality — wherein the philosopher engages in a dialogue with the camera, points to it, lets himself be shot from different angles, and watches it. He comments that it may not be only language that is a figure of thought in its own right, but that the cinematic image can play the same role. Thus, camera shooting can be a possibility of thinking with film, or thinking through film, it can be a different way of expressing/demonstrating theses and concepts, their contradictions, and mutual consents.

Different thinking

Avant-garde thinking, along with the Flusserian gesture, suggests that the camera need not/cannot be used only as a tool to capture reality and construct seamless narratives, but that it can be used to think elsewise/differently - subversively, expressively, experimentally, performatively. The disruption of the established practices of film language undermines the seemingly realistic impression of the film spectacle and draws attention to the reality of itself, the media gesture, the figure of thought of the film apparatus and material. The series of (counter)shots established by classical film narration can be disturbed by long shots or shots conducted in unusual directions, distances and angles, panoramic camera rotations, shooting with the help of atypical devices, techniques, and technologies. The moving image becomes not only extraordinarily physical and material, but also of thought; a film that contemplates itself, an autopoietic system, a self-movement of the film form that is not only a way of representation, but also a method of philosophical reflection. The camera thus becomes a (self-)reflexive gesture, a lateral gaze that reveals the possibilities of capturing and imaging and allows us to better reveal the reverse side of visible phenomena. Film as a closed space of mediation is opened. Thinking of such a stylized and performative film then provokes various phenomenological and ontological themes. The medium (the film) that has covered our perception/vision is not covered, but constantly reveals itself to us, allowing us to think with and through the film about our own situation in a media-saturated world.

Freeing the Camera

The present time (of many crises) is not only losing its originality and authenticity but is gradually leading to an alienation of the self and to the constant insinuation that anthropocentric and superior thinking about the world is only a rationalistic construct and may not last forever. More and more, we are forced to think about the world outside the subject, to think about the world without man, the world-without-us, about the thinking of others, but also about materiality as such, which is distancing itself from the human scale. The boundaries between the living and the non-living, the organic and the inorganic, the human and the non-human, as well as the ordered and the controlled and the non-orderly and the random, are beginning to dissolve. In this world, the camera may no longer be just a tool in the hand of the creator and a possibility of transforming vision in the manner of the avant-garde, but it can largely detach and become independent, productive, and performative. Its trajectory can be determined by wind or water flow, it can be triggered by automatic sensors, subject to non-living or non-human "cameramen". The technical images that have been perceived as "ours" exist to a large extent outside us and reach completely different (cosmic?) dimensions. Technique and technology thus direct our attention (independently from us) to dimensions of the living or inanimate world that are difficult, if at all, for us to capture in the form of theoretical concepts and considerations. The unusual camera views can then be combined or replaced by digital technologies that allow even greater escape from human influences and perspectives, from the representational function and existing reality. The artists' thinking and seeing is not superior to the image, but seeks to approach hitherto unimaginable structures, non-human media and materialities, and inorganic processes.

Utopian dystopia

Is it a utopia or a dystopia? Does the need to change the current thinking mean disaster, or can it be seen as a new opportunity? Wasn't/isn’t dystopia rather the "kinetic utopia" that Peter Sloterdijk writes about, which assumes that all world movement is merely the realization of our plans, and that nature continuously submits to human desires? What happens in the moment when it is — like the camera's gaze — so exhausted that it must change direction and hegemony? How can the moving image, to quote Donna Harraway, help us with this reversal of the non-order of "natural culture"? What can it show us, how can it prepare us, and what reflective figure can it provide? Can we get carried away by images and forget our usual structures of thought, oppositions, and obvious truths?

Let's try to follow the camera and its opinion.

Kateřina Svatoňová